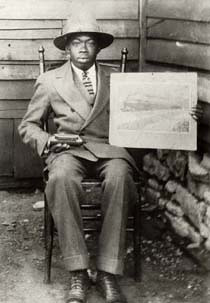

Now, Deford Bailey is where things start to get interesting. Not only the first African-American to appear on the Grand Ole Opry, but the first man to play, so the story goes, on the night that the Opry got its name (December 10, 1927), he's so little known that I can't predict if our visits for this post will go up (because people have heard vaguely of him and are curious) or will plummet (because people have not heard of him and are not curious). A harmonica player of the first rate (even if I can't really make any guess as to his influence on the titans of post-war blues harmonica, the Little Walters and James Cottons of the world) whose trademark was an imitation of a train engine that formed the backbone to his best-known song, the "Pan-American Blues." He was a fixture on the Opry in its formative years, before being kicked off in 1941 during the ASCAP/BMI war, when unable to perform his signature material, he came into conflict with Opry management.

"A victim of the licensing battle between ASCAP and the newly formed BMI in 1941, Bailey was told he could no longer play on WSM the tunes that he had played on the air for over 15 years and had made him famous. Instead he would have to play completely new ones on WSM [ed - the Opry's 50,000 watt station]. He did not fully understand what was going on and his simple reaction was that he would leave the show if he could no longer play his tunes. As a result he was terminated from the program; and although the licensing battle between the two groups was resolved a few months later, this effectively ended his performing career. He continued to play his harmonica on a daily basis and enjoyed entertaining friends and patrons of his shoe shine shop, but he seldom performed publicly after this." (http://defordbailey.info/biography)Following his (unwilling) exit from the Opry, he essentially quit public performing. He continued to run the shoe-shine business he had established with family in Nashville, and led a private life. He appeared several times at Opry "old-timers" events at the end of his life, urged on by friends interested in gaining him his (due) recognition from the Opry establishment, but aside from the 8 sides he cut in 1928 (in the very first recording session in Nashville!), he never again recorded professionally (a friend and amateur historian, David Morton, recorded conversations and harp playing in the 1970s, and these recordings are available here).

***

When I first came across Bailey's music in 2006 (thanks to Cantwell and Friskics-Warren's Heartaches by the Number: Country Music's 500 Greatest Singles), I found it nearly impossible to track down, even with the best web, torrent, and p2p sources at my disposal. I'm happy to report now that thanks to the exposure of the documentary "Deford Bailey: A Legend Lost," produced by National Public Television and aired on PBS in August 2005, and the amazingly comprehensive site maintained by Bailey's friend and biographer David Morton, that his music and his story are far more readily known now than even just a few years ago. And this, in a way, is one of the main reasons Lost Highway remains compelling (and in print) today. Guralnick's influence in helping to publicize Bailey in the late 1970s must have been important in reviving his legacy as a performer. Equally, it contributed to a greater awareness beyond the academic community (and a greater attention in the academic community, if the publication record is any evidence) to the influence of African-Americans and their culture and music in the development of "white" hillbilly and country music.

The importance of this was struck home to me when I was preparing the first of these posts, on Jimmie Rodgers. Looking for the Youtube link I eventually posted, I was surprised to find in the video comments section a very tense discussion going on about the "black" influence on Rodgers' songs and style. There were, to be sure, simplistic (if forgivably so, given the obvious connection of Rodgers; style, phrasing, and lyrics to the blues of his time period) arguments that Rodgers was "stealing" the blues. But there were also, much to my shock, a series of posts violently "defending" Rodgers from claims that he was influenced by black culture, arguing that country music was a "pristine" form of folk culture descended from the balladry tradition of the British Isles, transplanted to Appalachia. Now again, forgiving the first error (Rodgers was not Appalachian), there's truth to the "balladry" argument as well--there are strong connections in style and lyrical theme in early country that go back to Europe. No one disputes this. But the notion that Jimmie Rodgers was not influenced by contemporary African-American musicians he met and heard is patently absurd. That anyone would need to make this claim is also absurd (both in terms of readily available knowledge of his biography, and in terms of the obvious sonic debt).

The importance of this was struck home to me when I was preparing the first of these posts, on Jimmie Rodgers. Looking for the Youtube link I eventually posted, I was surprised to find in the video comments section a very tense discussion going on about the "black" influence on Rodgers' songs and style. There were, to be sure, simplistic (if forgivably so, given the obvious connection of Rodgers; style, phrasing, and lyrics to the blues of his time period) arguments that Rodgers was "stealing" the blues. But there were also, much to my shock, a series of posts violently "defending" Rodgers from claims that he was influenced by black culture, arguing that country music was a "pristine" form of folk culture descended from the balladry tradition of the British Isles, transplanted to Appalachia. Now again, forgiving the first error (Rodgers was not Appalachian), there's truth to the "balladry" argument as well--there are strong connections in style and lyrical theme in early country that go back to Europe. No one disputes this. But the notion that Jimmie Rodgers was not influenced by contemporary African-American musicians he met and heard is patently absurd. That anyone would need to make this claim is also absurd (both in terms of readily available knowledge of his biography, and in terms of the obvious sonic debt).The same, of course, is true for Bailey as well. Deford's formative musical experiences were with the same sorts for fiddle music being played in Georgia by Fiddlin' John Carson. These songs were were part of a shared pre-blues and pre-country musical tradition of "reels and breakdowns" (p. 51) that crossed ethnic and racial lines in the South, and that provided the raw material for both emerging styles. This relationship was encapsulated by one of the commercial releases RCA made of Deford's recording of "John Henry." Unlike the vast majority of records at the time, it was released as both a "race" and "hillbilly" side, with an African-American playing on one b-side, and a white harp player on the other.

Guralnick's book goes to great pains to make the reciprocal link between black and white Southern cultures in musical terms during the pre- and early post-war period. What the pay-off will be (and given that rockabilly and Elvis are up next, I have my suspicions) of this musical intersectionality will be the subject of many of my future posts in Reading Rock: Lost Highway.

Deford Bailey - Pan-American Blues

Deford Bailey - John Henry

Deford Bailey - Ice Water Blues

Deford Bailey - Davidson County Blues

Deford Bailey - Alcoholic Blues & It Ain't Gonna Rain No Mo'( these last are from the Morton recordings. I couldn't find the original version, although it looks to be available here. If I can find the original versions, I'll replace them.)

Some old-time songs mentioned as relevant to Bailey's musical development:

(Fare You Well) Old Joe Clark (here, by Fiddlin John Carson)

Lost John (here, by Burnett & Rutherford)

And the "hillbilly" and "race" b-sides:

Bert Bilbro - Chester Blues

Noah Lewis (who also recorded with Sam Chatmon) - Like I Want to Be

And please, please do take a small moment and poke your head in here, at the Morton site, to here some of the audio clips of Deford (musical and interview) he's posted from his private collection of personal recordings.

Posted by Brandon

No comments:

Post a Comment