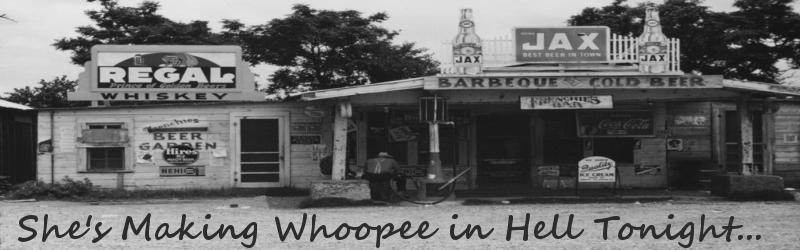

The Dean of American Rock Criticism

"Unless you are very rich and very freaky, your relationship to rock is nothing like mine. By profession, I am surfeited with records and live music. Virtually every rock LP produced in this country is mailed to me automatically, and I'm asked to go to more concerts than I can bear. I own about 90 percent of the worthwhile rock albums released since the start of the Beatles era, and occasionally I play every one of them, although I haven't heard half the LP's in my collection in six months. All this has a double-edged effect. On the one hand, I am impatient with music that is derivative and see through cheap gimmicks easily. On the other, I can afford to revel in marginal differentiation, delighting in odd and minor talents that might not be worth the money of someone who has to pay for his music."-Robert Christgau, "Consumer Guide #1," Village Voice, July 10, 1969

One of the priorities Lin and I had when we started this blog was to have a conversation about how much the way we consume music has changed since we both started becoming "music" people in the late 1990s. I'll let Lin speak for himself, but my strongest memories of that initial, exploratory phase almost always involved a local record store (often visited in lieu of attending my afternoon classes) and an old Sony boombox, the pride of my teenage years. I can remember playing my Replacements records at top volume before my father got home from work, sitting on the bed and reading the liner notes and memorizing biographical details about Bob, Paul, Chris, and little Tommy that no one would ever ask me about. I remember listening to Wilco's Summerteeth, turning the volume up and down while my father mowed the lawn, moving back and forth from my window to the driveway. I remember convincing my mother to let me sign up for the BMG service that sent you 10 free CDs if you payed full retail price on two more (and back in those days, full retail price was $18 or more--another reason no one I knew ever shopped at Sam Goody in the mall).

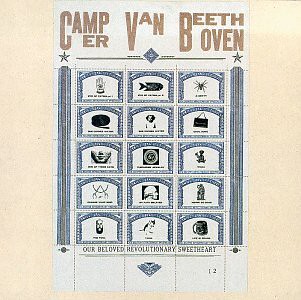

But mostly, I remember when I had no more CDs than would fit in a single copier paper box. They had personalities, it seemed--I knew where the scratches were, and which jewel cases had cracked fronts or broken tines in the little circle that secured the disc. I poured over every detail of every liner insert--no matter how little information there was to find. I had a clear sense of the value of my music back in those days. I knew what the investment meant to me, both in money and in time digging through the stacks. I remember the sheer joy of finding something I had read about at the library, or had been mentioned on one of my music listservs. Months of looking, of slipping away from my parents on vacations to stick my head into thrift stores and little music stores, checking the new arrivals racks at the used store back in La Crosse every week. When I found Camper Van Beethoven's Our Beloved Revolutionary Sweetheart that afternoon in the spring on 1999, it made my week. And I didn't even know what it was going to sound like.

But mostly, I remember when I had no more CDs than would fit in a single copier paper box. They had personalities, it seemed--I knew where the scratches were, and which jewel cases had cracked fronts or broken tines in the little circle that secured the disc. I poured over every detail of every liner insert--no matter how little information there was to find. I had a clear sense of the value of my music back in those days. I knew what the investment meant to me, both in money and in time digging through the stacks. I remember the sheer joy of finding something I had read about at the library, or had been mentioned on one of my music listservs. Months of looking, of slipping away from my parents on vacations to stick my head into thrift stores and little music stores, checking the new arrivals racks at the used store back in La Crosse every week. When I found Camper Van Beethoven's Our Beloved Revolutionary Sweetheart that afternoon in the spring on 1999, it made my week. And I didn't even know what it was going to sound like.

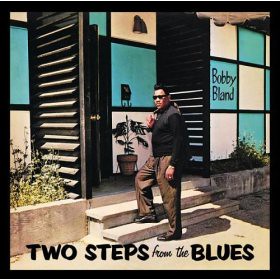

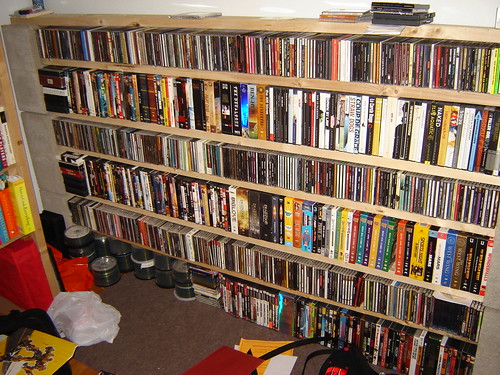

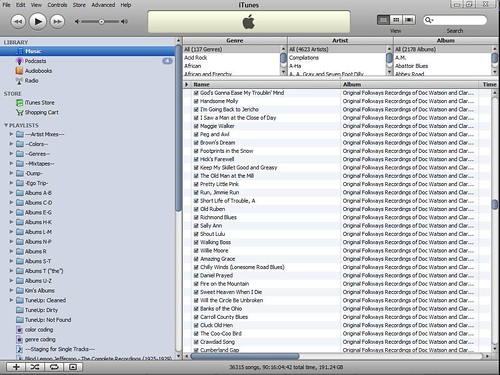

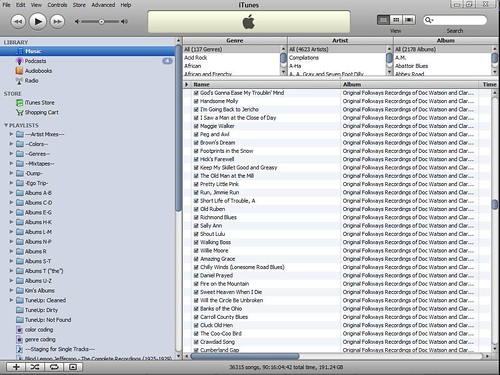

Now, after Lin's visit last week, I have 36,316 songs in my iTunes library. It's about 1800 separate "albums," but would take 1633 blank CD-Rs to contain its epic grandness. And Lin's collection is at least 25% bigger (a fact I chalk up solely to his collection of Orthodox church singing, and that year I was in Nigeria without internet access). Christgau's collection circa 1969 was probably bigger, but mine is almost certainly broader (this was, I'm reasonably sure, before he discovered Papa Wemba and Franco and became America's greatest proponent of African pop music), containing all manner of music from the rock "canon," but also nearly complete discographies for many of the major artists of the rock and roll era and a staggering collection of blues, classic country, and soul box sets. When music became so easy for me to get, my response (as, I suspect was Christgau's) was to become nonsensically cosmopolitan in my tastes. While it's easy enough for me to summarize my basic preferences and my favorite musical themes (I'm going to forgo the word "genre" here, for reasons that will soon become apparent), my collection is probably more diverse that 95% of the people in this country who consider themselves music fans. That said, there are still entire styles of music that are basically unrepresented (ambient and all the various forms of electronica, classical), which means occasionally I'm accused of parochial tastes by people in casual conversations about music. The notion that a man who owns the Complete Hank Williams Collection, a half dozen Fela Kuti records, everything Elton John recorded between 1970 and 1976, the complete Mississippi Sheiks' recorded works, two Conway Twitty albums, four Ice Cube platters and a disc of early M.I.A. & Diplo mixes is a little crazy, but there it is anyway.

Really, I find it all a little alienating. It sounds ungrateful, but there are days I miss being able to identify every CD I own by comparing the pattern of scratches on the underside. It's harder to forge the strong emotional connections I had with the records I listened to three times a day for six months in 1996 when I feel compelled to check out some of my new haul everyday. I rarely get through complete albums anymore--and frankly, as much as I really like pre-war black string band music, I don't think I'll every play the entire four and a half hour Mississippi Sheiks playlist in a single sitting. The irony is that this is all happening just as my life is changing more generally, in a way that makes my vastly expanded musical knowledge less and less relevant to my identity in the minds of most of my acquaintances.

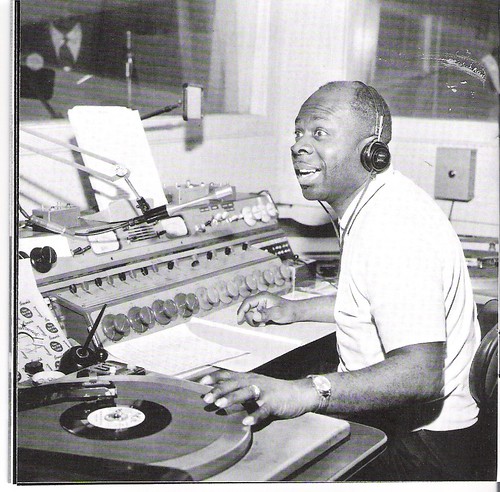

When I was in college, I probably never owned more than 350 albums, but music was a constant part of my everyday self. I deejayed dance parties and on the college radio station, and always insisted on curating the music at dorm room gatherings, even when they consisted on nothing more that six people crammed onto a futon staring down at a case of warm Coors Light. The songs I played when I was with my friends, or when I was at parties, were more than just the songs I liked--they were an attempt to signal what I was all about (and perhaps, get laid in the process). When music is such an investment, as it was for me on my college budget, you don't invest flippantly in the new thing, no matter how big it's getting. You build a collection from the bottom up, with a limited selection that you're sure you'll continue to like (or, as sure as you can be at 20) and that will tell the appropriate story about who you are. But now, just when I have the ability to wow the masses with a truly diverse, exotic, and free-wheeling collection that fits in my pocket, I don't have any more parties to go to. None of the other grad students in my program have expressed any real interest in pop music in the broader sense--most conversations I've had about music bog down in the first two minutes. Someone will tell me their favorite band, and I'll start talking about my new reggae compilation, and then they'll politely excuse themselves. What people want to know about me--as a scholar, as a teacher, as a married guy in his late 20s--has very little to do with my music taste. The only difference between me and the rest of the iPodded masses is the size of my headphones (and no, that's not a metaphor for anything).

When I was in college, I probably never owned more than 350 albums, but music was a constant part of my everyday self. I deejayed dance parties and on the college radio station, and always insisted on curating the music at dorm room gatherings, even when they consisted on nothing more that six people crammed onto a futon staring down at a case of warm Coors Light. The songs I played when I was with my friends, or when I was at parties, were more than just the songs I liked--they were an attempt to signal what I was all about (and perhaps, get laid in the process). When music is such an investment, as it was for me on my college budget, you don't invest flippantly in the new thing, no matter how big it's getting. You build a collection from the bottom up, with a limited selection that you're sure you'll continue to like (or, as sure as you can be at 20) and that will tell the appropriate story about who you are. But now, just when I have the ability to wow the masses with a truly diverse, exotic, and free-wheeling collection that fits in my pocket, I don't have any more parties to go to. None of the other grad students in my program have expressed any real interest in pop music in the broader sense--most conversations I've had about music bog down in the first two minutes. Someone will tell me their favorite band, and I'll start talking about my new reggae compilation, and then they'll politely excuse themselves. What people want to know about me--as a scholar, as a teacher, as a married guy in his late 20s--has very little to do with my music taste. The only difference between me and the rest of the iPodded masses is the size of my headphones (and no, that's not a metaphor for anything).

So ultimately, this is my introduction to a new line of inquiry we'll be undertaking here at She's Making Whoopee in Hell Tonight--given the inordinate amount of music we all have, and given that this makes us not in the least cool, and furthermore, given that we must have acquired it because we want to listen to it, who do we turn all those files into something accessible, something useful? How do we make the music work for us?

The first tentative steps in this direction will probably focus on how we classify and sort our music, starting with a discussion of "genre." Anyone who's had the ill-fortune to import a record into iTunes knows that the Gracenote database they use to tag the information onto the songs uses an unwieldy, dense tangle of genre nomenclature--a taxonomy rooted in neither how we listen to music nor how artists make it. How can we classify our music? Is it worth trying, and if so, what's the payoff (hint: for me, it's having a way to divide up my music into workable chunks I can listen to on shuffle, the way that I used to listen to the radio. This is how I'm forced to take on all that new music in manageable, well-programmed chunks)? We'll almost certainly be looking at the academic literature on music genre taxonomies going on in various information systems journals (because that's what we do). Stay tuned.

The first tentative steps in this direction will probably focus on how we classify and sort our music, starting with a discussion of "genre." Anyone who's had the ill-fortune to import a record into iTunes knows that the Gracenote database they use to tag the information onto the songs uses an unwieldy, dense tangle of genre nomenclature--a taxonomy rooted in neither how we listen to music nor how artists make it. How can we classify our music? Is it worth trying, and if so, what's the payoff (hint: for me, it's having a way to divide up my music into workable chunks I can listen to on shuffle, the way that I used to listen to the radio. This is how I'm forced to take on all that new music in manageable, well-programmed chunks)? We'll almost certainly be looking at the academic literature on music genre taxonomies going on in various information systems journals (because that's what we do). Stay tuned.

Franco et le T.P.O.K. Jazz - Liberté

The Mississippi Sheiks - Bootlegger's Blues

The Mississippi Sheiks - Sittin' On Top of the World

Camper Van Beethoven - Waka

Camper Van Beethoven - Eye of Fatima (pt. 1)

Oh, and for the dozen or fewer of you who care, Reading Rock: Lost Highway will be back with a vengeance between now and Tuesday, with a new post and those promised .zip files. Holler.

Posted by Brandon

But mostly, I remember when I had no more CDs than would fit in a single copier paper box. They had personalities, it seemed--I knew where the scratches were, and which jewel cases had cracked fronts or broken tines in the little circle that secured the disc. I poured over every detail of every liner insert--no matter how little information there was to find. I had a clear sense of the value of my music back in those days. I knew what the investment meant to me, both in money and in time digging through the stacks. I remember the sheer joy of finding something I had read about at the library, or had been mentioned on one of my music listservs. Months of looking, of slipping away from my parents on vacations to stick my head into thrift stores and little music stores, checking the new arrivals racks at the used store back in La Crosse every week. When I found Camper Van Beethoven's Our Beloved Revolutionary Sweetheart that afternoon in the spring on 1999, it made my week. And I didn't even know what it was going to sound like.

But mostly, I remember when I had no more CDs than would fit in a single copier paper box. They had personalities, it seemed--I knew where the scratches were, and which jewel cases had cracked fronts or broken tines in the little circle that secured the disc. I poured over every detail of every liner insert--no matter how little information there was to find. I had a clear sense of the value of my music back in those days. I knew what the investment meant to me, both in money and in time digging through the stacks. I remember the sheer joy of finding something I had read about at the library, or had been mentioned on one of my music listservs. Months of looking, of slipping away from my parents on vacations to stick my head into thrift stores and little music stores, checking the new arrivals racks at the used store back in La Crosse every week. When I found Camper Van Beethoven's Our Beloved Revolutionary Sweetheart that afternoon in the spring on 1999, it made my week. And I didn't even know what it was going to sound like. Now, after Lin's visit last week, I have 36,316 songs in my iTunes library. It's about 1800 separate "albums," but would take 1633 blank CD-Rs to contain its epic grandness. And Lin's collection is at least 25% bigger (a fact I chalk up solely to his collection of Orthodox church singing, and that year I was in Nigeria without internet access). Christgau's collection circa 1969 was probably bigger, but mine is almost certainly broader (this was, I'm reasonably sure, before he discovered Papa Wemba and Franco and became America's greatest proponent of African pop music), containing all manner of music from the rock "canon," but also nearly complete discographies for many of the major artists of the rock and roll era and a staggering collection of blues, classic country, and soul box sets. When music became so easy for me to get, my response (as, I suspect was Christgau's) was to become nonsensically cosmopolitan in my tastes. While it's easy enough for me to summarize my basic preferences and my favorite musical themes (I'm going to forgo the word "genre" here, for reasons that will soon become apparent), my collection is probably more diverse that 95% of the people in this country who consider themselves music fans. That said, there are still entire styles of music that are basically unrepresented (ambient and all the various forms of electronica, classical), which means occasionally I'm accused of parochial tastes by people in casual conversations about music. The notion that a man who owns the Complete Hank Williams Collection, a half dozen Fela Kuti records, everything Elton John recorded between 1970 and 1976, the complete Mississippi Sheiks' recorded works, two Conway Twitty albums, four Ice Cube platters and a disc of early M.I.A. & Diplo mixes is a little crazy, but there it is anyway.

Really, I find it all a little alienating. It sounds ungrateful, but there are days I miss being able to identify every CD I own by comparing the pattern of scratches on the underside. It's harder to forge the strong emotional connections I had with the records I listened to three times a day for six months in 1996 when I feel compelled to check out some of my new haul everyday. I rarely get through complete albums anymore--and frankly, as much as I really like pre-war black string band music, I don't think I'll every play the entire four and a half hour Mississippi Sheiks playlist in a single sitting. The irony is that this is all happening just as my life is changing more generally, in a way that makes my vastly expanded musical knowledge less and less relevant to my identity in the minds of most of my acquaintances.

When I was in college, I probably never owned more than 350 albums, but music was a constant part of my everyday self. I deejayed dance parties and on the college radio station, and always insisted on curating the music at dorm room gatherings, even when they consisted on nothing more that six people crammed onto a futon staring down at a case of warm Coors Light. The songs I played when I was with my friends, or when I was at parties, were more than just the songs I liked--they were an attempt to signal what I was all about (and perhaps, get laid in the process). When music is such an investment, as it was for me on my college budget, you don't invest flippantly in the new thing, no matter how big it's getting. You build a collection from the bottom up, with a limited selection that you're sure you'll continue to like (or, as sure as you can be at 20) and that will tell the appropriate story about who you are. But now, just when I have the ability to wow the masses with a truly diverse, exotic, and free-wheeling collection that fits in my pocket, I don't have any more parties to go to. None of the other grad students in my program have expressed any real interest in pop music in the broader sense--most conversations I've had about music bog down in the first two minutes. Someone will tell me their favorite band, and I'll start talking about my new reggae compilation, and then they'll politely excuse themselves. What people want to know about me--as a scholar, as a teacher, as a married guy in his late 20s--has very little to do with my music taste. The only difference between me and the rest of the iPodded masses is the size of my headphones (and no, that's not a metaphor for anything).

When I was in college, I probably never owned more than 350 albums, but music was a constant part of my everyday self. I deejayed dance parties and on the college radio station, and always insisted on curating the music at dorm room gatherings, even when they consisted on nothing more that six people crammed onto a futon staring down at a case of warm Coors Light. The songs I played when I was with my friends, or when I was at parties, were more than just the songs I liked--they were an attempt to signal what I was all about (and perhaps, get laid in the process). When music is such an investment, as it was for me on my college budget, you don't invest flippantly in the new thing, no matter how big it's getting. You build a collection from the bottom up, with a limited selection that you're sure you'll continue to like (or, as sure as you can be at 20) and that will tell the appropriate story about who you are. But now, just when I have the ability to wow the masses with a truly diverse, exotic, and free-wheeling collection that fits in my pocket, I don't have any more parties to go to. None of the other grad students in my program have expressed any real interest in pop music in the broader sense--most conversations I've had about music bog down in the first two minutes. Someone will tell me their favorite band, and I'll start talking about my new reggae compilation, and then they'll politely excuse themselves. What people want to know about me--as a scholar, as a teacher, as a married guy in his late 20s--has very little to do with my music taste. The only difference between me and the rest of the iPodded masses is the size of my headphones (and no, that's not a metaphor for anything). So ultimately, this is my introduction to a new line of inquiry we'll be undertaking here at She's Making Whoopee in Hell Tonight--given the inordinate amount of music we all have, and given that this makes us not in the least cool, and furthermore, given that we must have acquired it because we want to listen to it, who do we turn all those files into something accessible, something useful? How do we make the music work for us?

The first tentative steps in this direction will probably focus on how we classify and sort our music, starting with a discussion of "genre." Anyone who's had the ill-fortune to import a record into iTunes knows that the Gracenote database they use to tag the information onto the songs uses an unwieldy, dense tangle of genre nomenclature--a taxonomy rooted in neither how we listen to music nor how artists make it. How can we classify our music? Is it worth trying, and if so, what's the payoff (hint: for me, it's having a way to divide up my music into workable chunks I can listen to on shuffle, the way that I used to listen to the radio. This is how I'm forced to take on all that new music in manageable, well-programmed chunks)? We'll almost certainly be looking at the academic literature on music genre taxonomies going on in various information systems journals (because that's what we do). Stay tuned.

The first tentative steps in this direction will probably focus on how we classify and sort our music, starting with a discussion of "genre." Anyone who's had the ill-fortune to import a record into iTunes knows that the Gracenote database they use to tag the information onto the songs uses an unwieldy, dense tangle of genre nomenclature--a taxonomy rooted in neither how we listen to music nor how artists make it. How can we classify our music? Is it worth trying, and if so, what's the payoff (hint: for me, it's having a way to divide up my music into workable chunks I can listen to on shuffle, the way that I used to listen to the radio. This is how I'm forced to take on all that new music in manageable, well-programmed chunks)? We'll almost certainly be looking at the academic literature on music genre taxonomies going on in various information systems journals (because that's what we do). Stay tuned.Franco et le T.P.O.K. Jazz - Liberté

The Mississippi Sheiks - Bootlegger's Blues

The Mississippi Sheiks - Sittin' On Top of the World

Camper Van Beethoven - Waka

Camper Van Beethoven - Eye of Fatima (pt. 1)

Oh, and for the dozen or fewer of you who care, Reading Rock: Lost Highway will be back with a vengeance between now and Tuesday, with a new post and those promised .zip files. Holler.

Posted by Brandon